Why are our gas prices at a gas station tied to the speculative stock market? When did that happen and why?

Judy Etzler

Dear Reader,

This is a great question, especially in light of current circumstances here in the U.S. Gasoline consumption is down; at the same time, gasoline production in the U.S. is reaching record levels. Classical economics tells us gas prices should be falling. However, with gas prices at the pump reaching $4 per gallon and presidential candidates spouting all sorts of nonsense, who knows what to believe?

Mr. Econ decided to call on a long-time friend and expert in this field to help him answer this question. Dr. Cyrus Bina of the University of Minnesota-Morris is a recognized expert on the economics and geo-politics of oil, and is the author of “The Economics of the Oil Crisis, and most recently, “Oil: A Time Machine—Journey Beyond Fanciful Economics and Frightful Politics.” Dr. Bina has helped us all understand this very intricate subject. However, Mr. Econ takes full responsibility for his answers.

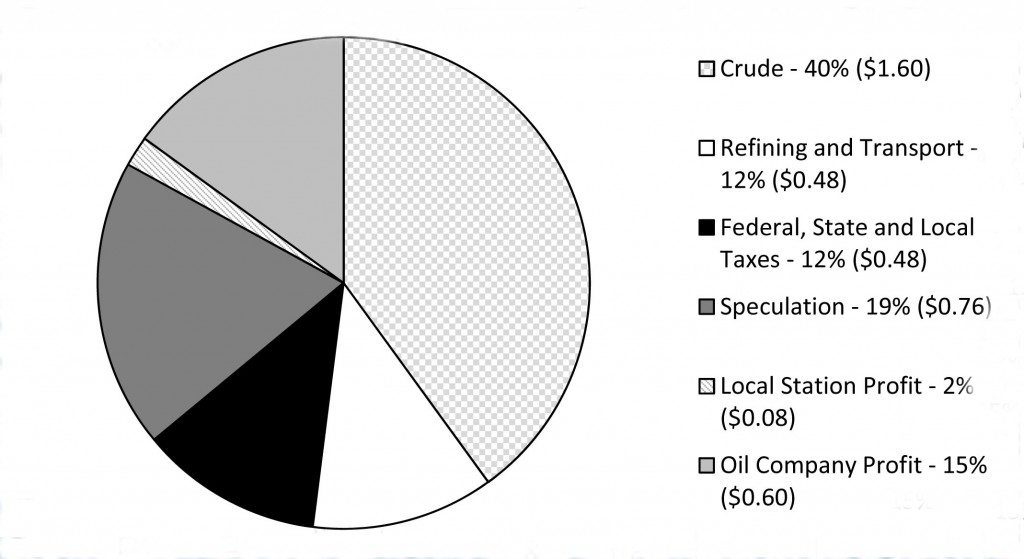

First, we must consider that the price of crude oil that goes into motor fuels represents only about 40 to 50 percent of the cost of gasoline at the pump. In addition to motor fuels, there are many more and larger demands for products made from crude oil, like everything made of plastic or fiberglass and agricultural chemicals from pesticides to fertilizers. Manufacturers of the these products and large oil users, like airlines, purchase massive quantities of refined oil by long-term contract in order to insure the supply they need to satisfy their customers and hopefully, by purchasing early, a lower price.

Recently, the role of speculators has been put forward as a major cause in rising gas prices. Everyone from President Obama to Congress to even the investment firm Goldman Sachs has declared that speculators have driven up the price of gasoline at the pump anywhere from about $0.45 per gallon (Federal Reserve study) to $0.70 per gallon (Goldman Sachs).

Until recently, those companies that use some form of oil to produce their products held the vast majority of long-term oil contracts. With recent political and economic events, that has changed to where “speculators” now hold at least 50 percent of the long-term oil contracts. The reason for this shift is pretty complex but has a lot to do with what is going on around the world.

Usually Saudi Arabia serves as sort of a balancing force for the price of oil. If prices began to rise, the Saudis would increase production. As prices rose about a year ago, though, Saudi Arabia did not increase production. Instead, they held production steady or may have even slashed production. No one really knows for sure, as the Saudis don’t make their exact production figures public. In effect, the Saudis have become speculators themselves, believing that by withholding oil from the market, they will be able to sell it for more at a future date.

Iranian oil has been pulled out of some sectors of the oil market due to the controversy surrounding that country’s recent nuclear exploits. The threat of war or some sort of military action over Iranian nuclear policy has everyone a little edgy. Hence, people are worried about what might happen to this critical source of oil and oil coming from this region of the world in general.

Another factor is world demand. For example, China went from a net exporter of oil to a net importer of oil in the 1990s. This didn’t have a large effect, as their imports weren’t that large. Today, China imports 3.7 million barrels of oil per day, making it the third largest oil user in the world. Hence, it now has the ability to affect oil market prices.

Then there is the cost of refining the crude oil. Refineries need maintenance, so every so often some of the oil refineries get shut down. Also, because of seasonal demands and season blends of gasoline mandated in order to satisfy public policy like the Clean Air Act, refineries are shut down to affect the switchover in refining processes. This limits the amount of gasoline available.

Because of all of these factors, price gouging cannot be ruled out. Gasoline is a commodity people need and for which most people are very willing to pay just about any price. Hence, any classical economic notion of perfect competition in the market place is just a theory or a dream, and by no means reflects reality.

Finally, there are elements in fuel prices like taxes and minimum mark-up laws.

Combining all of these factors, the price of gasoline at the pump is “de-coupled” from the price of crude oil we often hear quoted on the nightly news. In the current case, we see that the price of gas is being affected by, among other things, real or imagined nuclear weapons. Even a Wall Street speculator, Goldman Sachs, is admitting to about $0.70 per gallon of price gouging. If that’s what they are willing to admit to, Mr. Econ has to ask what the number really is.