Transcript edited by Pierce Butler

Transcript edited by Pierce Butler

This is the sixth in a continuing series of excerpts from transcripts in the collection of the Samuel Proctor Oral History Program at the University of Florida.

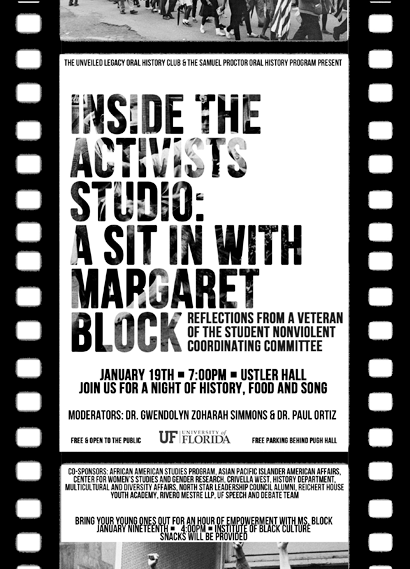

Lifelong civil rights activist Margaret Block was interviewed by Paul Ortiz on September 18, 2008.

I got involved in the movement like in – when I was about 10 years old, I used to hang around with this man named Mr. Amzie Moore. They organized the Regional Council on Negro Leadership, and I was aware of something being wrong because listening to my parents and everybody talk about it. I wasn’t able to do anything until 1961 when I graduated from high school. Then I joined the movement. I didn’t join SNCC until ’62 because we didn’t have nothing in Cleveland [Mississippi] in 1961 but the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and I joined it. That was we were teaching people how to read and write and how to take that test that you had to take from the state of Mississippi interpreting the Constitution.

That’s what we had to teach, the literacy test, which was insane. You know, one registrar asked how many bubbles is in a bar of Ivory soap, just dumb stuff. That’s the most rewarding thing I’d ever done in my life, was teaching that citizenship school. It was the idea of me teaching my elders how to read and write. I taught all over the Delta and Rosedale and all over, Cleveland and Shaw, just all these little towns in the Delta. That was in ’63, ’62 and ’63. When we did that, that was way before Freedom Summer.

Well, SCLC was more Christian, religious, more spiritual than SNCC was, and SCLC was, they were the educational. You know, like they gave us training and they would get us out of jail and stuff like that. They led the mass movements and stuff, too. But SNCC was a lot of vibrant young people. You know, they were students, and I had met all – I didn’t even go to college until real late because I was in the movement and my brother got kicked out of Mississippi Valley State for trying to organize a SNCC chapter on campus. So I figured, what’s the use. Mmm-hmm. So I tell people I didn’t get an education by going to college. I got an education working in the movement and coming in contact with people like Hollis and John Lewis and my brother and Amzie Moore and Diane Nash and Septima Clark.

SNCC was, we were risk-takers. We would do stuff and people, Dr. King would be goin’, you know, “just look at you,” because we were not afraid to challenge nobody. So that’s what I like to emphasize. We used to party a lot, not all the time. But we used to have parties and just have fun and, you know, to relieve all that tension and stuff that was going on with being shot at and being chased. So it was more, well, it was more for young people, SNCC was.

Emmett Till was the reason we couldn’t wait to get big enough to join a movement. He said that he was the fire, he started the fire. That’s what they did when they killed Emmett Till. Because I remember Amzie Moore and Medgar Evers, I grew up around those guys. You know, Medgar used to live in Mound Bayou with Dr. Howard when Dr. Howard was a surgeon. So when Emmett got killed, Medgar and Amzie Moore dressed up like they were field hands and went out to the fields and were talking to people, investigating it around which was brave, and crazy, and suicidal.

Music was extremely important to the movement. If it wasn’t for the Freedom Songs, we would take a church song and, you know, just change the words. Those are all church songs we were singing up there but we just changed the words. But that was important, the music in the movement. The music was the glue that kept the Civil Rights Movement together. And it was the best organizing tool that we had, because we would be singing those songs at a meeting and people would pass by and hear us singing and say, oh, you guys going to sing that song next week? And we’d tell them yeah and we’d have the church full because people would enjoy the Freedom Songs.

So those Freedom Songs are really important. They’re at the Smithsonian Institute. Bernice Reagon recorded them down there in Atlanta at the SNCC song-whatever they had in ’63 or ‘62, you know, all those years ago. But anyway, Bernice, who sang with Sweet Honey in the Rock… Bernice Reagon – Bernice Johnson, when I knew her. Yeah, she recorded all those songs,

Kids going to school now, in my hometown, they know nothing at all about my brother Sam who is an icon in the movement. He was featured in African American National Biography by Henry Louis Gates. People, I think they just don’t care. It’s not just the children. It’s the adults. And it’s not good, either, that you don’t even know your own history and you got icons walking around now that you could talk to, like Ms. Rogers or just people still around that was in the movement and that’s being treated like, OK, we’re going to half-teach it and we’re going to do that half-truth thing with it.

Yeah, we had a shoot out. It was August the 7th, 1964. We had taken the Brewer Brothers from Sharkey Road, which was out from Glendora. We had taken them over to Charleston to the courthouse to vote, and we expected trouble because we knew those people – that was one of the strongholds of the Klan, too, Tallahatchie County.

So we knew it was going to come down the next night, and what did we do? We went. The Brewers, all of them were well-armed. So when they came, when these Klan came down there at night, we were out in the country and we was on this farm and it was one long road. When we came out from the country, they was gonna shoot at us.

And they were so surprised when we shot at them first. They took off. We had our spotlights. This lady named Ms. Elsie Brewer, she turned on a big ol’ spotlight, turned it on, and they didn’t know what to think of, and when we shot at them, we didn’t hear nothing else from them.

They would harass us on the radio and stuff, but we didn’t hear anything else about them coming out there to shoot nobody. Because we let them know that we were fully prepared to shoot it out with them. We even made Molotov cocktails.

Now, one time – that’s the time when Stokely was out on the project with me out there in Tallahatchie, and Stokely tell me, we gonna make some Molotov cocktails, and I’m going, mmm-hmm. He’s telling me, gimme the cash money, we makin’ Molotov cocktails tonight, and I’m looking at him, never have been nowhere but to Chicago and Memphis and Jackson all my growing up years. Pretty soon I went, Stokely, I don’t drink, and I don’t want no cocktail. I thought he was talking about something to drink.

O: Some people would find it surprising because the official ideology of the movement was nonviolence, but in this particular case, you’re saying the Brewer family –

We made exceptions. Oh, that was just SNCC, the Student Nonviolent – I didn’t tell them I was nonviolent.

I went on and carried the fight on to San Francisco when I moved—finally had got ran out in ’66. My nerves had gotten just bad, you know, tired of being threatened and shot at and just going through stuff. So I had went to San Francisco. But I went on with the fight out there, joined the war, you know, Vietnam, the anti-Vietnam War and that, no intervention in Central America, helped write Proposition J, which we got put on the ballot. You know Prop J, where we – the first city to divest our pension funds and stuff from South Africa.

O: OK. Why did you come back [after 31 years]?

Well, my mom got sick, and then I just had to be, I don’t know. My children were grown when I came back, and I own a house and, you know, rather than struggle to pay extremely high mortgage rates in northern San Francisco, I moved back down here to take care of my mom. Then I decided that the fight ain’t over with here. I’m still fighting.

Yeah, like they’re charging kids to go to school, public school. That’s another fight I had. I was working for the Mississippi Center for Justice, the Youth Justice Center out of Jackson, and, yeah, they’re charging kids school fees to go to public schools. Charging them, yeah, $10 enrollment for elementary school, $17.50 for middle school, and then it just went through the roof when they went to high school, like paying for those classes

They know they got to have English, they know they got to have chemistry, and they charge for that stuff.

It’s an incredible injustice. It’s like a poll tax on education or something. Then there’s no accountability for the money because each parent when you go to whatever school you go to, you have to pay the money to the cashier, the secretary at the school. It doesn’t go into general budget fund. They do what they want to do with it, and God only knows what they doing with it. D

An audio podcast of this interview will be made available, along with many others, at www.history.ufl.edu/oral/feature-podcasts.htm.

The Samuel Proctor Oral History Program believes that listening to first-person narratives can change the way we understand history, from scholarly questions to public policy. SPOHP needs the public’s help to sustain and build upon its research, teaching, and service missions: even small donations can make a big difference in SPOHP’s ability to gather, preserve and promote history for future generations.

Donate online at www.history.ufl.edu/oral/support.html or make checks to the University of Florida, specified for SPOHP, and mail to PO Box 115215, Gainesville, FL, 32611.