by Tyler Benjamin

One woman told a small group why she stopped drinking Miller High Life at 19 and started going for the Pabst Blue Ribbon they were holding now. Most of the men had beards or at least sideburns that stretched down to their chin. Almost everyone had something pierced. They shared their stories of activism over white wine in biodegradable cups.

Stetson Kennedy would have loved this scene.

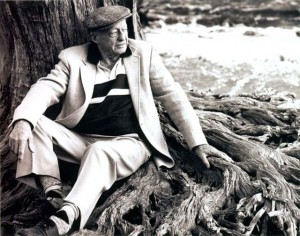

Kennedy, a white native of Florida, was a writer and activist for oppressed communities in the South ranging from blacks during the Jim Crow era to migrant workers in more recent times. The accomplished man died in August at age 94.

He recently revealed that he could speak another language when he gave part of a speech to migrant workers in Spanish.

He commissioned a Jewish flag-maker in New York to make a flag with a swastika, which he eventually unfurled behind officials from a German company seeking more American investment just after World War II.

The Klan still has a price on his head after he infiltrated their organization, handed over some of their deepest secrets to the FBI and then to a radio show because he found out the FBI was in bed with the Klan too.

“In the end, we really thought that he was going to live forever,” said Paul Ortiz, director of the Samuel Proctor Oral History Program at the University of Florida. “He had beaten everyone else. There was no reason to believe he couldn’t cheat death.”

Ortiz was the guest speaker at the 18th birthday of the Civic Media Center in October who detailed Kennedy’s life and called on an audience of around 40 people to continue Kennedy’s legacy of thorough research and powerful writing.

Kennedy’s wife, Sandra Parks, who sits on the CMC’s board and turned 71 the same day of the event, said Kennedy donated thousands of books to the center because he wanted ordinary people to have access to his work.

She explained that Kennedy chose the CMC over one of the most prestigious incubators of social activists in the nation, the Highlander Research and Education Center in Tennessee, because the Gainesville center was “in the university’s face and not on a mountaintop in Tennessee.”

The event, co-sponsored by the oral history program and the CMC, mirrors Kennedy’s belief in story telling as a vehicle to capture and preserve the knowledge of what many that night referred to as “ordinary people.”

Ortiz explained that Kennedy believed in the combination of education and activism to combat oppressive forces like racism. He believed that economic inequality led to the greatest oppression, not a lack of knowledge or outright hatred.

Using that as a springboard, Ortiz called on the audience to not be timid in their writing, asking students especially to step up to the plate where people like Kennedy once went to bat for those who weren’t even allowed to play.

“This book is as powerful as a picket sign,” Ortiz said, holding up “Jim Crow Guide,” one of Kennedy’s books.

Ortiz, Parks and the CMC’s co-founder and director discussed Kennedy’s unwavering trust in what his wife called “the uncommon good sense in ordinary people.” Each of them reiterated Kennedy’s best advice: pick a cause and stick with it.

While he never demanded commitment to world-changing causes from anyone, Parks said, Kennedy himself didn’t shy away from them. He cared deeply about human rights, the preservation of traditional cultures and looking after the environment.

As a young man, Kennedy chose this life when he literally walked away from a table set with privileges like his white skin and his family’s ties to the Ku Klux Klan.

One morning over breakfast, Kennedy’s sister asked him if he’d rather be with black people than with his family, Ortiz said. Kennedy answered yes and left the house.

Ortiz made clear that Kennedy’s work collecting stories with the Works Project Administration, a New Deal program, taught him the truth behind economic disadvantage but also about the power of listening. Kennedy couldn’t look away from injustice, and this was rooted in the story-collecting fieldwork he did when he left UF at just 21.

In his travels, Kennedy saw a Florida scarred with open-faced phosphate mines and forests destroyed by the turpentine industry, according to Ortiz. He met poor, unskilled blacks who could sing and tell incredible stories, but who couldn’t leave to make a better living because that just wasn’t the way it worked.

After Ortiz spoke, Joe Courter, the CMC’s co-founder and director, asked members of the audience to share what the center means to them. A few mentioned how they didn’t find a place like the CMC in other cities. One woman said it was her spiritual home, and one man explained it’s the reason he settled in Gainesville. All spoke with misty eyes and great appreciation.

James Schmidt, a CMC coordinator, said he signed up to get involved at the center exactly 18 years ago. He called the center “an incubator for social activists,” and he connected the past and present.

“The value of the Civic Media Center is that young folks in this college town get involved, start volunteering, learn about a whole world of ideas, find that thing that Stetson talked about and then they go into the world,” Schmidt said.

It’s that forward, “into the world” sentiment that Ortiz wanted to convey Tuesday night. To that end, alongside the CMC’s oral history project, Ortiz said an oral history project anchored in Kennedy’s life is in the works.

Kennedy’s legacy of intense and prolonged activism sat quiet but present in the books that surrounded the audience Tuesday night, and the bursting biography of a citizen committed to justice came to life in Ortiz’s call-to-arms.

Parks summed up Kennedy’s fervor in one simple sentence, something she said he used to conclude his own presentations and something she used to conclude her words that night.

“If any of you see a hopeful movement, call me collect.”