by samuel proctor oral history program

by samuel proctor oral history program

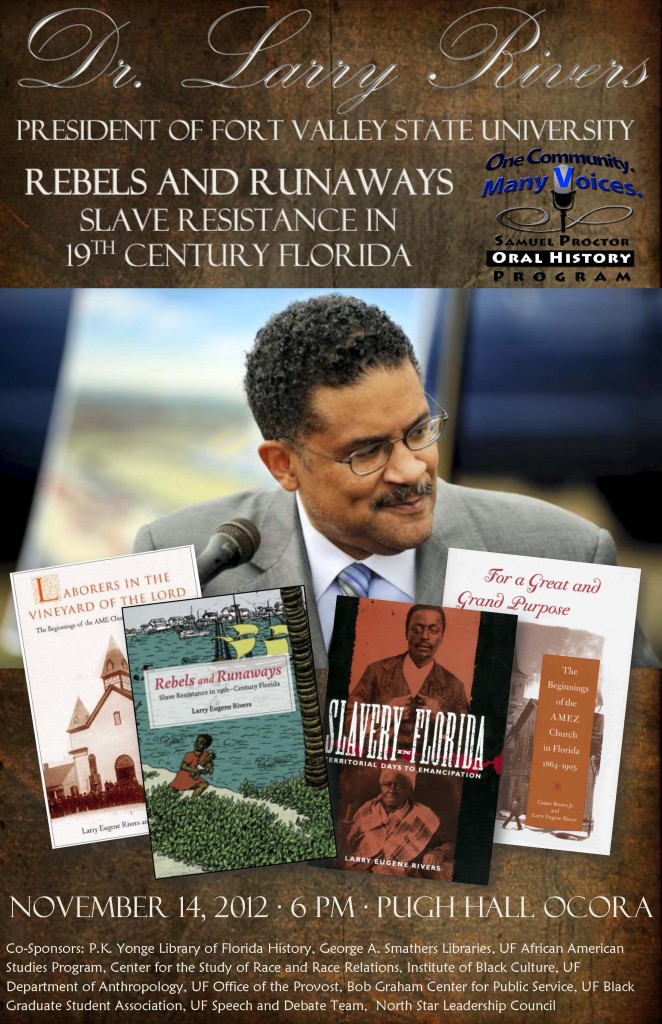

On the evening of Wednesday, November 14, the University of Florida hosts Dr. Larry Rivers, President of Fort Valley State University, for a public program at Pugh Hall at 6 pm on his new book, “Rebels and Runaways: Slave Resistance in Nineteenth-Century Florida.” President Rivers will also be signing copies of his books “Rebels and Runaways” and “Slavery in Florida.”

Dr. Rivers is an award-winning author of numerous books and essays on African American history, including “Slavery in Florida: Territorial Days to Emancipation.” Under his leadership, Fort Valley State University has risen to become one of the top-ranked Black Colleges in the United States and was recently ranked 9th among the top regional public colleges in the South by U.S. News and World Report.

Larry Rivers earned his PhD at Carnegie-Mellon University in 1977. For more than twenty years, Dr. Rivers taught history at Florida A & M University, ultimately receiving the rank of Distinguished University Professor. During that time, he held a series of administrative appointments, leading to his selection in 2002 as Dean of the FAMU College of Arts and Sciences. Dr. Rivers is a member of Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity, Inc., the Fort Valley State University National Alumni Association, Inc., the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, Sigma Pi Phi (The Grand Boule) Fraternity, the Urban League and Prince Hall Masonic Lodge.

Parking for the event at Pugh Hall is free. For those who cannot attend, the event will also be Live Streamed by the Bob Graham Center for Public Service on November 14th at 6 pm eastern standard time, and available on their homepage: http://www.bobgrahamcenter.